The Problem With Virtual Urban Planning

Can metaverse designers agree on whether instances or continuous regions are preferable?

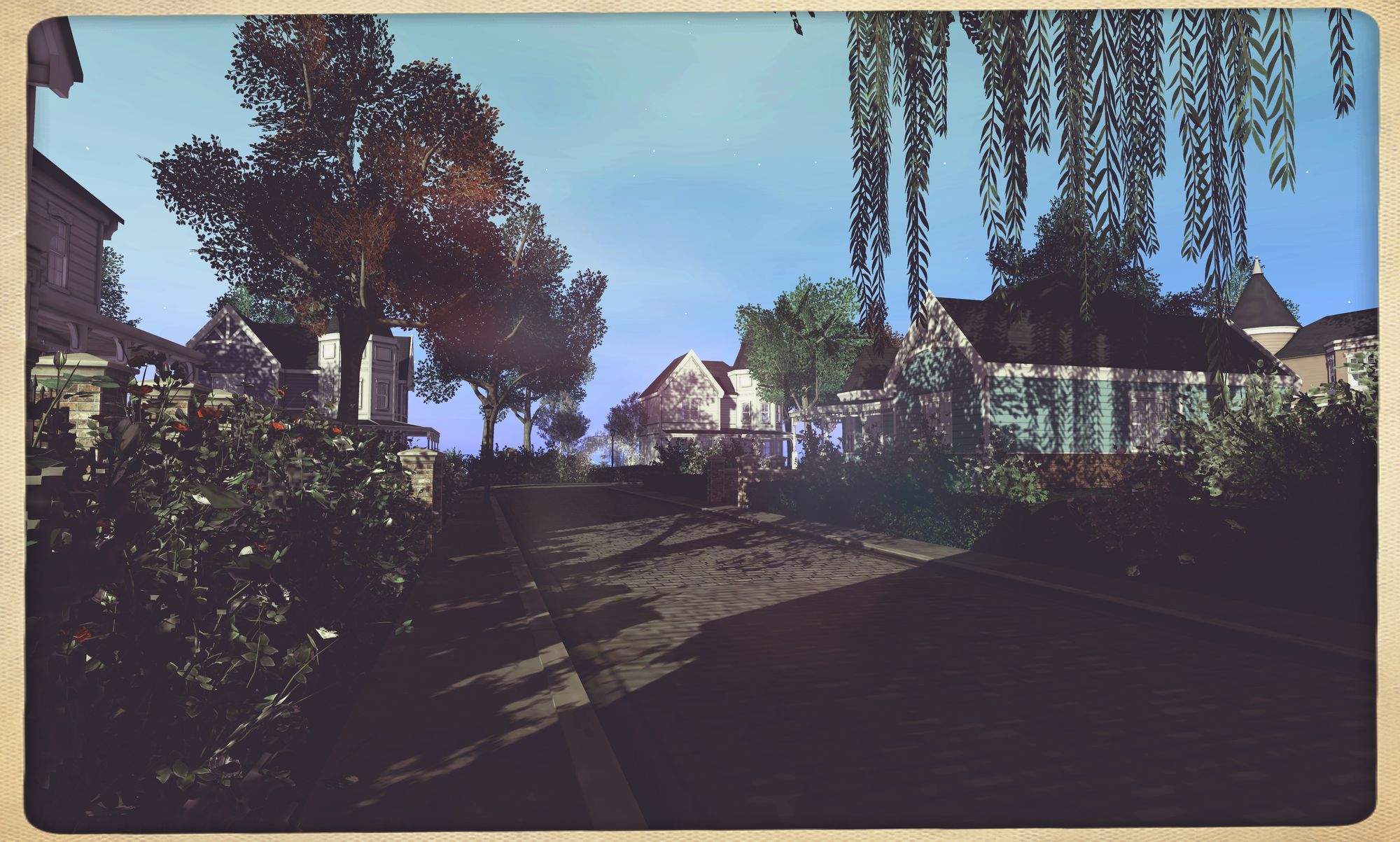

Second Life's new initiative to attract users to their grid, Linden Homes, is a pretty array of slightly-varied plots stretched over connected sims to form a region. Rivers and oceanic byways curl around them, roads snake through them. Trees dot the land. There are parks and occasional landmarks to visit. For ten dollars a month, you can own a slice for yourself and decorate your house as you wish.

When you teleport in, it takes a minute. Everything needs to load. This is not an instance-centric platform, and so what users spawn on individual plots next to yours are still rendered by you. You will wait until your internet has downloaded what you set your camera to render, and then you'll hopefully be able to walk through without suffering from any lag.

It's usually after you've put the last finishing touches on your home that you'll settle down and peer over your fence at your neighbors. Some of them visit the same big-name decor stores that you do--oh, nice, you remember that sofa. You bought that one last year. Or the photo set on the wall you thought about purchasing when it was on sale, but you didn't. You will either covet or quietly hiss at their choices, some you might even disdain for how resource-intensive they are.

Then you'll wander outside, down the street, around the block. You'll explore the neighborhood on foot, maybe in a spawned vehicle. You'll visit the landmarks you saw earlier and local beaches. If you have friends that live nearby, you'll visit them as well. You'll hear the group chatter of the neighborhood association because that's where they all truly are, bickering at each other over small things.

And then you'll click on the x on the window and go do something else, because there's no one else outside and you didn't really move here to be alone.

Gogo doesn't see everything in the positive-and-negative light that I do. Friends for years now, she and I have a formidable combined viewpoint when it comes to platform design and what works. Separately, we are a tale of two different users.

Where I am a rather intense person and a natural troubleshooter, she views things through the sharp eyes of The Consumer, the one waiting for a game's potential to be reached so she can plug in her credit card.

If you build a platform and want her demographic to register and throw money at you, she's the person you can ask about what it would take to get your game to that point. She's going to tell you: make it easy, and make it hot. How hard is it for her to use your point-and-click interface to create a gorgeous avatar she will then want to dress up over and over? Are there good camera tools to take pretty shots of her new self? Are there options for makeup implementation? How much can she set herself apart visually from the other users, yet remain fashionable? That's important too.

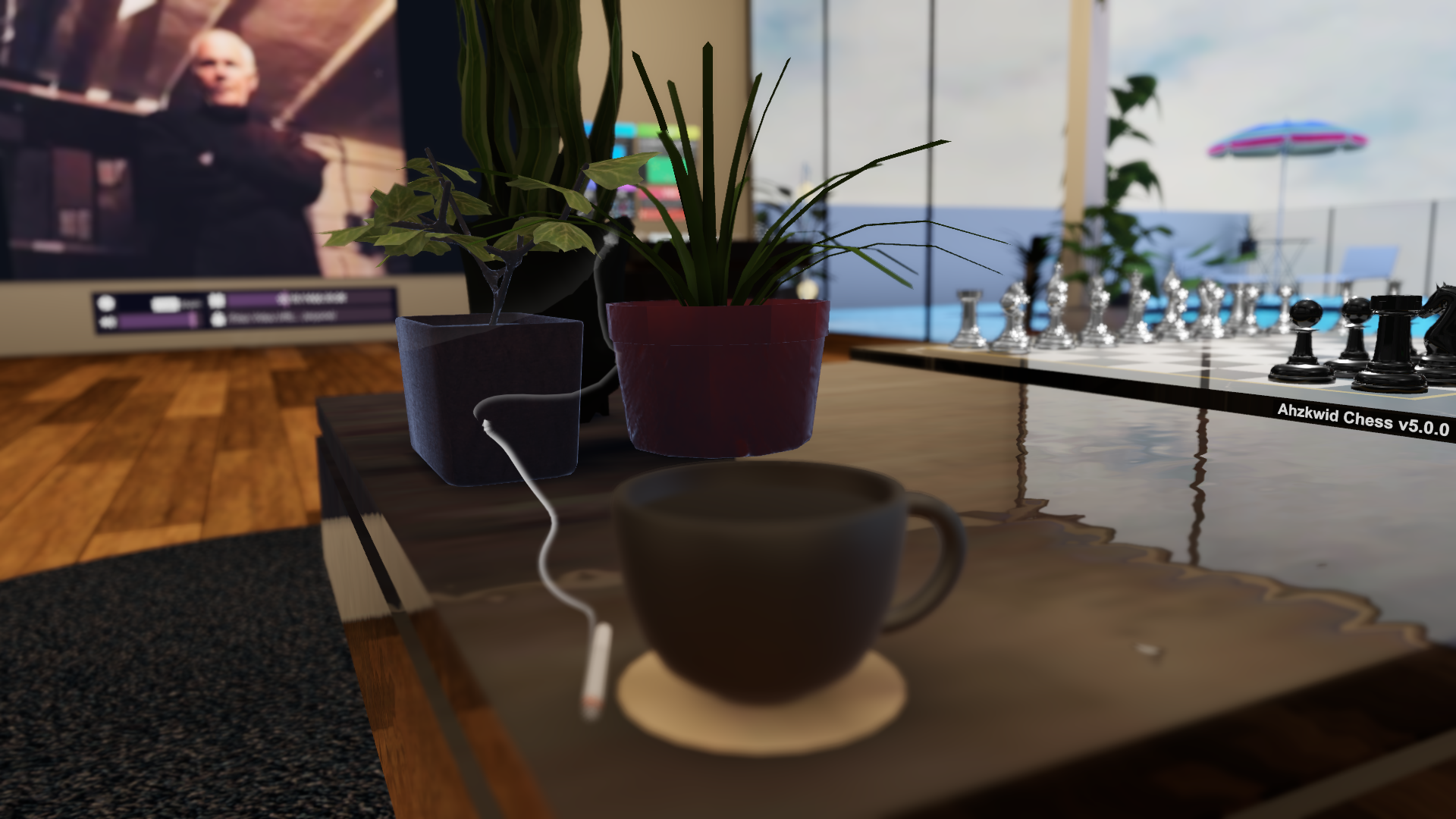

To her, the setup of Linden Homes is what she wants. She decorates hers to tell a story, much like what some of my old neighbors did: a picturesque baking set left on a perfectly color-coordinated counter, a fireplace going with an inanimate dog sleeping next to it, flowers arranged outside that aren't too heavy in appearance. Everything clean and pastel. Her everyday outfits go perfectly this, her collection of carefully placed items matching the story of her own style. Sometimes your neighbors want you to peer inside their homes. It's a game of one-upping and envy, of Pinterest feeds brought into a 3d experience.

But what she enjoys most are the public constructs connecting everything. "I love living in a region with roads that I can walk or drive on," she says. "I can feel like I'm going somewhere in a realistic way, rather than just teleporting there."

When we first registered for Linden Homes together, I promised to pick a region close by so we could walk to each others' houses. Whenever she said "come by", I didn't teleport there, even though I could have. I walked because even I wanted to see the homes and ever-changing yards along the way. I liked seeing how decor changed along the streets over time, through the holidays and seasons.

And when Gogo was not logged in, I would go on a tour to see what other people's yards looked like. Those tours could stretch to an hour, if you really felt that adventurous.

The downside are the neighbors that don't get along.

The ones that put up eyesores, the ones that don't read rules before decorating, or spawn something with a script that threatens to lag the sim. The ones that erect an overly-zealous security system that will auto-eject people who aren't even on their property. When no one else is able to log in without getting crashed or removed, it's a problem.

Through our time living as neighbors, Gogo and I came to rely on group-pooled reports of yards that were not just spawning one little ugly item, but things that were as big as lighthouses that actually interrupted roads or bodies of water. Because of what the moderators of the game dealt with, it would take a long time for a report to go through. I got tired of it; when I purchased VR, I moved away to VRChat. Doing so felt like packing up and flying to the next virtual continent over. Gogo and I still talk, but it feels like long-distance communication because we no longer interact as we used to. I send back private threads showing what I'm doing, and she still takes pictures of our old stomping grounds.

Now, I live in a home contained within its own map. No neighbors unless I build their home next to mine. If someone wants to visit my house, they don't need to join the map I'm on, but they can if I let them. Instances are a godsend to me, the boon for introverts. There's no one to peer over and ask me to teleport to their private hottub party. They can't unless I friend them.

Instances can be lonely sometimes, but I would argue even a connected world can feel the same way. Just because you're standing in the middle of a crowd, doesn't mean you suddenly have a community you're a part of.

Lately, the topic of metaverse urban planning has popped up again on Twitter. New designers, new outlooks. But with this comes a lack of information on what previous game designers have created and the lessons they've learned. Let's go over them again.

You can have a connected community of houses, but it won't run itself. Nor will it keep itself company. Staff-created events can help to bring those users out again and mingling with one another. Can't get them out of their homes? Pick some of the more influential, extroverted ones to show up. Those extroverts want to be around others and there's a good chance they'll drag their friends with them.

You can have a community of user-based content, but that doesn't mean it'll all be pretty. Never shoulder the burden of creative content comletely on the users. They will eventually disappoint you or go somewhere else. Some examples should originate from the creative team to inspire the rest of the userbase.

You can have a world of instances, but that doesn't mean those instances will all be public (or that even a good amount of them will). Community spaces with exclusive experiences (meaning, prefabs or games that can't be duplicated to other maps) can bring back users again and again. VRChat's Spookality event often brings users around in droves to look at maps and talk to each other at the main hub, for example.

Users love to look at themselves, whether in 2d or in VR. Give them a reason to step out of their home map or plot. And that part is up to you. We're now coming into the age where more online users are learning their way around Unity and Unreal Engine. If they can create their own single player game, what do they need you for? Only you can provide that answer.

Interested in supporting The Metaculture? You can do so here.