That Time I Saw A Functioning Grave In Second Life

On the edge of the internet, you're likely to find anything.

Have you ever been on a virtual road trip? It's a lot like a physical one. You set a destination, pack whatever you think you're going to need, and head out for the sights.

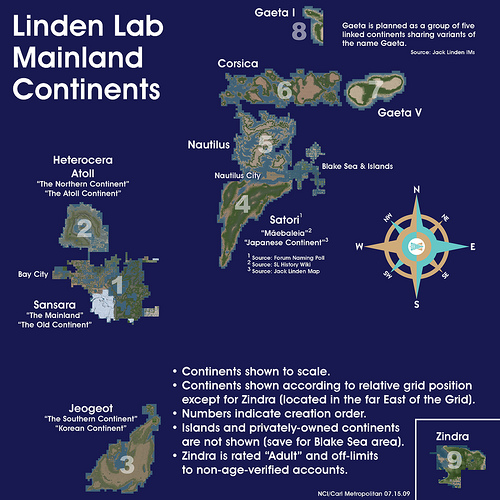

Second Life has masses of land from when they used to develop digital cities. Dubbed "Mainland", these regions have existed since 2003. The oldest landmass is called DaBoom (named after a street in San Francisco, and possibly the big bang theory of the universe). Visit these 20-year-old sims now, and you'll find structures created with simple primitive shapes. Back then, they didn't have complex mesh files to create worlds with; that technology came along later.

Mainland is still inhabited by people who don't prefer the suburban comforts of Second Life's newer, pristine Bellisseria housing project. It's also for people who like purchasing multiple parcels to settle, but also don't want to pay about $200 a month for their own private virtual island.

Mainland continents are connected, though not always continuously by water. Here's a map from back in the day:

So what do you find when you take a road trip to Mainland? Ancient houses still being paid for on a monthly basis. Wacky advertisements for services long gone. Old structures created with the same building-block primitives that could be optimized, but won't due to a sense of historical preservation. Older versions of Second Life housing projects, standing on their own, the rest vacant. Clusters of parcels that users have bought out to erect private cities. Obscure digital mansions hidden by giant walls of trees, their mysteries untold.

Some of these curiosities prevent unapproved users from inspecting them more closely, because they only allow certain individuals or groups to access them. Everyone else gets a big ugly banline in their face. Turn elsewhere, though, and it's like the Danny Brown song: house, field, field. Field, field, house. Abandoned house, field, field.

And along the shore are lonely towering compounds. Much like in the physical world, these face the sea and speak to no one else. Beyond that, the ocean parcels are either for sale, or set aside for the public to travel on. To this day, there are still small towns dedicated to those who enjoy virtual boating.

It was on a random Mainland road that I stopped to look at a parcel for sale. Across the street was a small, obscure new-age church. I paid it no attention until a user appeared next to it.

Here's the thing about virtual worlds the public has yet to embrace: shit's weird out there, sometimes far weirder than what you encounter on the flat internet. We've built most of Web 1.0 and 2.0 in a constructed way, that you encounter most of those weirdos on a website. You click and block them if their text is annoying enough.

In a 3D manifestation of the web, it gets even weirder. There are layers to spatial interaction that can't be replicated in text posts on Bluesky or Threads. Society still can't parse this, even after more than 30 years of virtual worlds existing. That's why movies which briefly include characters wearing VR headsets never address what it is they're looking at unless it's a sci-fi show.

The avatar that appeared across the street from me was tall and lanky. He wasn't styled with anything that was made past the year 2006. My avatar was looking perfectly like 2017, around when all of this happened. He inclined himself in my direction, slowly walking across the street towards me.

I couldn't remember his name, but he started the conversation in a perfectly amiable manner. What brought me here? I was traveling, I explained. I expected him to ask if I wanted to see his church, but instead he suggested something else. Come see a place where my friend is, he said. Then he disappeared and invited me via teleport. I knew it wouldn't end well, but I was feeling chaotic enough to go.

So, I teleported with him.

We appeared in front of a strangely-constructed pyramid in another part of Mainland. Flanking either side were more old stores that couldn't possibly be frequented anymore--more prims in the construction, signs advertising free clothing and sex toys, dollar-package avatar clothing sets and skin textures from shops that shuttered years ago. The pyramid stood apart from the square buildings, garishly golden with colorful hieroglyphs. Two glass doors finished the entrance. It was like a mini Las Vegas style casino.

The foyer of the pyramid building held items in special display cases. As we walked, my guide explained the place was actually a tomb. I accepted this explanation to mean it was a historical recreation and responded in kind. No, he clarified. It was a tomb. It was real. Someone was resting there.

Every Second Life player knows how to access a special minimap to show where other players are in the area. It's helpful for navigating crowds or dark spaces when you don't have other nameplates showing. As soon as my guide explained the building was one big grave, I brought up my minimap. Sure enough, there was someone else lingering on the far end of the parcel.

Still feeling punchy enough to see this adventure to the end, I followed the avatar into the last room. That's when a woman's nameplate began to fade into view.

Two years prior, I lost a Second Life friend to cancer. At the time, my girlfriends and I inhabited our own virtual island. We mourned her loss--she was the earthy anchor to our lively bunch, the native Hawaiian who loved water and recreated a piece of her Hilo home so we could take part in Hawaii's spirit with her. I left a virtual gravesite for her by the shore. It stayed there for years until another friend decided to stop paying for the island to try out Bellisseria instead.

The woman in the Egyptian-style casket in front of me had her arms crossed over her chest. She had black hair, red lipstick, and aged-but-stately clothing. The guide explained she had died physically, but wanted her avatar to rest in the building. He obliged and saw to the arrangements. I checked her profile. She had a history. She seemed to have truly existed at some point. I don't know what the guide meant by inviting me to see her tomb, but I wasn't entirely dispassionate of the notion. At the same time, I was still a little unnerved by it.

Was it an extension of his grief? There's a documented history of virtual gravesites in different video games when people pass on. No one pops out of nowhere to invite strangers to visit their dead friends' virtual resting place, though. It occurred to me that he might have received some kind of system notice when I stopped on the road, and figured it was a good way to speak to someone new.

Maybe he isolated himself like I did after he lost his friend. I did that for some time afterwards. The rest of Second Life meant nothing to me when my friend passed away. But with enough time spent in isolation, one becomes gradually unfamiliar of how to reach out to others.

The internet is weird. We try to collectively ignore it and carry on as if its weirdness is not an extension of ourselves, but everything about the internet speaks to what an odd species we truly are. Especially social media. Especially spatial platforms. The internet may look distorted to us in all of its manifestation, but we can't say we haven't created it in our own image.

I thanked the gentleman for his time, left the building, and got back on my NPC horse to ride down the road. Wherever that guide is, I hope he's doing alright. I never came across the church or tomb again.